Diana L. Burley, Ph.D., Vice Provost for Research at American University (AU) where she is also Professor of Public Administration and Policy and Professor of IT & Analytics, will join the Internet Governance Lab as a Distinguished Faculty Fellow.

Faculty Co-Director Dr. Laura DeNardis on Gallup and Knight Foundation's Out of the Echo Chamber podcast

Internet Governance Lab Faculty Co-Director Dr. Laura DeNardis joined Jonathan Rothwell in the latest episode of Gallup and Knight Foundation’s podcast, Out of the Echo Chamber, discussing internet privacy, security and freedom. Rethinking Freedom When the Internet Is Everywhere: A Discussion With Laura DeNardis.

Internet Power and Control May Fall Simply Into China’s Lap

Faculty Co-Director Dr. Derrick Cogburn presents work on Entity Extraction & Topic Modelling with WordStat

On June 17, 2020, Provalis Research, a Canadian research company specializing in text analytics tools, hosted a discussion with Internet Governance Lab Faculty Co-Director Dr. Derrick Cogburn on entity extraction and topic modeling techniques drawing on his work examining large data sets from the Internet Governance Forum.

Beginning with an overview of two key inductive/exploratory text mining techniques – entity extraction and topic modeling – using WordStat – content analysis and text mining tool, Dr. Cogburn’s presentation situates these techniques within a broader discussion of data science and the voluminous amounts of textual data being enabled by the ongoing information revolution. He then introduces tools, techniques, and approaches to text mining, along with the CRISP-DM project management approach before presenting a brief snapshot of a project using entity extraction and topic modeling to understand twelve years of transcripts from the United Nations Internet Governance Forum (IGF). Dr. Cogburn closes the discussion with a hands-on demonstration of entity extraction and topic modeling using WordStat.

Watch the presentation below.

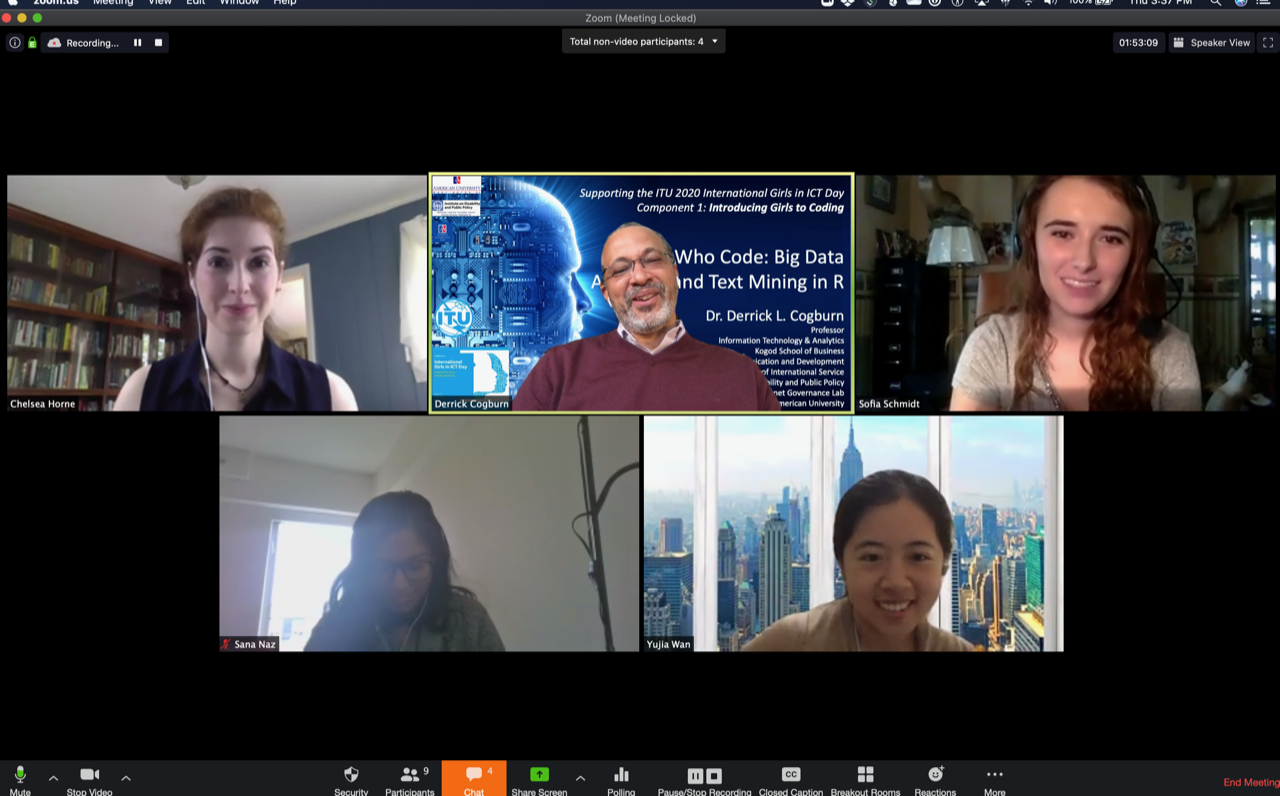

Women Who Code: Big Data Analytics and Text Mining in R and RStudio #GirlsInICT

On Thursday, April 23, 2020, the Internet Governance Lab, in support of the 2020 International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) International Girls in ICT Day (#GirlsInICT), organized a globally distributed session on “Women Who Code: Big Data Analytics and Text Mining in R and RStudio”.

Click here or on the image below to watch a recording of the session.

Organized by Internet Governance Lab Faculty Director Dr. Derrick L. Cogburn, Professor of Information Technology and Analytics and International Communication in the Kogod School of Business and School of International Service at American University, and Executive Director of the AU Institute on Disability and Public Policy, the discussion focused on the growing importance of big data analytics broadly speaking, and text analytics in particular while demonstrating the power of coding in the open source data analytics language R, programming the free RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE), and highlighted a range of packages that substantially extend the capabilities of R.

Following a practical overview of how to install and write code in R and RStudio, the session moved to five presentations from five female scholars, demonstrating the analytic and descriptive power of the programming language for research on a wide range of topics and disciplines. The lineup included:

Ms. Yujia Wan

IDPP Research Associate, Masters of International Affairs, School of International Service

Topic: “What’s Behind the Great Firewall? Differences between Baidu and Google in Searching Results”

Ms. Sana Naz

IDPP Research Associate, MS Analytics, Department of Information Technology and Analytics, Kogod School of Business

Topic: “Data Analytics and Predictive Modeling in R”

Ms. Dana Meyers

Masters of International Affairs, School of International Service

Topic: ”Key Issues in 2020 US Presidential Campaigns: Comparing Professed Themes to Actual Messaging on Twitter”

Ms. Sofia Schmidt

Masters of U.S. Foreign Policy & National Security, School of International Service

Topic: “Identifying Push Factors in Northern Triangle Migrant Interviews”

Ms. Chelsea L. Horne

Professorial Lecturer in the Department of Literature at American University; Doctoral Program, School of Communication; Faculty Fellow, Internet Governance Lab

Topic: “Governing Truth: An Analysis of “Post-Truth” Discussions of “Fake News” at IGF”

Doctoral Fellow Erica Basu Defends Dissertation on Digital Privacy Advocacy and Data Protection Policymaking in India

Dr. Erica Basu

By Sarah Palaia | April 17, 2020

How do you protect the data and privacy of half a billion internet users in the world’s largest democracy? India recently undertook that challenge, and SOC PhD graduate Erica Basu studied the process as it unfolded. Her research reveals how conflict and cooperation between government and non-governmental actors, and their use of communication platforms to inform and influence public opinion, shaped data and privacy laws.

For Basu, looking at her home country was an obvious choice—she already understood many of the factors, cultural and political, that would influence how India approached internet governance. By making a case study of the effort to write a new data and privacy law, she hoped to understand how much influence civil society organizations could have in the process. More generally, she was interested in how actors in a democracy use a “diverse range of communication tactics” as levers to intervene in policymaking.

Basu’s research found that all actors, including civil society, government and internet companies took advantage of communication channels to inform and influence public opinion. They used both traditional and digital media extensively, from town halls to Twitter. The Indian government, for its part, used digital platforms to communicate about the proposed law and to invite outside parties to comment on proposals.

Basu also found that the policies advocated by civil society organizations were likely influenced or constrained, at least in part, by the priorities of the private sector companies funding them. Private sector funding of think tanks, and partnerships between the government and private sector, created substantial overlapping interests that were not transparent. She said, “When you research the funding flow then you realize that…private sector money is being funneled through foundations.”

Finally, she argues that asymmetries of power limited communication and reduced civil society’s influence on policy. While the government used both digital and non-digital communication channels extensively, it chose not to publish public comments, breaking with established practice. In addition, the government used concerns about national security, law and order as a rationale for shutting down some online discussion, which led to a “narrowing of the civil society space and quelling of dissent.” She found that, ultimately, the Indian government holds policymaking power. In spite of opposition, the proposed law includes expansive rights for the government.

Basu’s work offers valuable insights for anyone studying issues of internet governance. Lessons learned from the India case study lead her to recommend, above all, that researchers “always look at the power asymmetries and the power structures between different actor groups.” She added, “I think that is a good lens to have when you’re studying any kind of technological issue and how it impacts societies.”

Before entering the PhD program, Basu also completed a Master’s degree at SOC. She credits the scholarship and generous teaching style of Professor and Interim Dean Laura DeNardis for drawing her into the program: “She inspired me to look at the internet as the next frontier where this was going to be the main space for interaction … as citizens both of our own countries and as global citizens.”

Doctoral Fellow Aras Coskuntuncel Defends Dissertation on Information Control Strategies in Turkey

Dr. Coskuntuncel with Lab Faculty Director and Interim Dean of SOC Dr. Laura DeNardis

By Sarah Palaia | March 19, 2020

As the Turkish government and its supporters solidify power and suppress dissent in the country, the ability of protesters and journalists to organize and share information over digital platforms is more important than ever. Watching events unfold, observers view webcasts and read tweets and assume that new digital communication technology keeps information flowing freely. The work of recent PhD graduate Aras Coskuntuncel helps us understand that, in real life, the story is not so simple.

Coskuntuncel’s research challenges the prevailing narrative that digital communication technologies tend to favor free speech and democratic processes, and he offers a new framework for understanding how non-democratic actors use “control points” to censor and limit the flow of information.

Using Turkey as a case study, Coskuntuncel explored the struggle between competing groups to control information during moments of social upheaval. He found that while dissidents and journalists used digital platforms to try to resist censorship, ruling elites were deploying the same technologies to censor and limit the flow of information. Far from undermining traditional structures, new technology may have helped those elites perpetuate their hold on power.

The new PhD graduate also contributes a unique analytical framework for understanding these dynamics. The framework comprises five “information control points” critical to manipulating the flow of information:

Instrumentalizing media through ownership structure

Privatizing censorship and surveillance by taking advantage of the businessmodel of the digital media

Networking surveillance

Employing direct censorship and legal political attacks

Networking information campaigns

The framework provides a powerful tool for researchers and democracy advocates looking to better understand the mechanisms of control in the digital era. Coskuntuncel hopes it will also help people “envision more democratic alternatives to today’s communication systems.”

Prior to entering the SOC PhD program, Coskuntuncel earned his master’s degree in media studies from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. While living in Turkey, he worked for the Hurriyet Daily News in Istanbul as the diplomacy and foreign news editor. Those experiences left him well prepared to launch an ambitious PhD project.

Coskuntuncel attributes the success of his dissertation, in part, to the scholarship and mentorship of AU SOC faculty. He says, “Our faculty’s approach, expertise, and their tireless guidance and close attention are what make AU’s PhD in communication second to none.” He points to the many professors who provided assistance and mentorship, including his adviser and dissertation committee chair, Laura DeNardis, Professor Emerita Kathryn Montgomery, PhD Program Director Patricia Aufderheide, Chair of Communication Studies Division Aram Sinnreich, and Professor Ericka Menchen-Trevino.

Girls in ICT Day 2020 Goes Virtual

International Girls in ICT Day is an initiative backed by ITU Member States in Plenipotentiary Resolution 70 (Rev. Busan, 2014) to create a global environment that empowers and encourages girls and young women to consider studies and careers in the growing field of information and communication technologies. Resolution 70 calls for all ITU members to celebrate and commemorate International Girls in ICT Day on the fourth Thursday of April every year.

This year, as we face unprecedented challenges around the COVID-19 pandemic, we will be commemorating Girls in ICT Day virtually, via our website and social media channels (@internetgov on Twitter) with the hashtag #GirlsinICT.

Check out this introductory message from Doreen Bodgan-Martin, Director of the ITU Telecommunication Development Bureau, and an AU alum!

Internet Governance Lab Calendar of Events (April 2020)

The Rise of Big Tech in India

On September 6 & 7th, 2019, I participated in a Cyber Policy Lab convened by Tandem Research in Goa, India on the Rise of Big Tech in India. The plenary session attempted to lay a broad roadmap for defining and conceptualizing Big Tech in India, focusing on its power and influence across policy circles and the everyday lives of Indian citizens.

The big questions that emerged from the plenary session were: (1) whether Big Tech is even a relevant category for India vis-à-vis the dominance of American and Chinese tech globally and in India, and (2) if India is ready institutionally (in the private and public sectors) to manage its growing digital economy and Big Tech writ large?

There was a recognition that while the use of the adjective "big" is not new, such as past narratives about big pharma, big tobacco, and big business, it carries a negative connotation in relation to tech, as evidenced in narratives ranging from "tech euphoria" to "tech lash." This is also largely driven by the power, scale, and speed of digital tech developments and the negative externalities of pervasive data collection that these systems are premised and rely on. To this point, one speaker noted how iconic US brands like Apple and Facebook began as countercultures that morphed into gigantic global cultural forces themselves. Meanwhile, others pointed out the degree to which Big Tech and the state are not as antagonistic as media narratives would have consumers and citizens believe. Indeed, even in the wake of the Snowden disclosures, American tech companies continue to partner with the Indian government's Digital India initiative, especially in rural India.

The first thematic session was an attempt to map the Indian Internet ecosystem across actors, interests, and influence. Intense debate ensued regarding whether Indian Big Tech is even a relevant category, not simply because of the dominance of US companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, as well as China’s Alibaba, but more recently because of the influx of foreign equity and tech funding into India's start-up ecosystem from the likes of SoftBank, Tencent, and Google's Next Billion Users Unit. Some workshop participants likened these developments to the spice trade of the 1600s, which brought foreign traders to India and ultimately led to the establishment of British imperialism for 300 years. Similarly, some attendees argued that Indian public policy was historically driven by the top 10% of the urban educated elites who favored more left-leaning policies, but that the new India would have to include the aspirations and demands of a more diverse population who would make up the next billion Internet users and digital consumers. Another important insight focused on the extent to which research in India is led by tech companies as opposed to academic centers. This is partly due to increased funding of academic and civil society events and research from tech companies like Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and TikTok, including digital literacy programs in rural India.

Others opined on the myth that Big Tech and multinational corporations are against privacy. They argued that robust privacy policies are now viewed as a competitive advantage. Frighteningly, many pro-market and nationalist actors feel that for a developing economy like India, domestic entrepreneurial innovation should be stated by the government as a national priority and not be sacrificed to cater to individual privacy and data protection demands. These attendees recommended that technologists "infiltrate" government policy circles and "cultivate" influential actors in the policy space to educate legislators, policymakers, and bureaucrats about digital technologies to achieve more market-friendly policy objectives.

The second session focused on current policy/regulatory interventions and their likely consequences. The session began with a mapping of all the policies in place and in the pipeline including the IT Act of 2000, the proposed Personal Data Protection Bill, the draft e-Commerce Bill, the Reserve Bank's 2018 Notification of Storage of Data Policy, 2000’s draft Intermediary Liability Rules of IT Act,the draft ePharmacy Regulation, 2017’s FDI Policy, 2014’s National Telecom Policy, the Companies Accounting Bill of 2017, and the IRDAI Regulations regarding storage of data. Data localization was a major point of contention between the participants. Surprisingly, pro-market participants favored data localization on the basis of national sovereignty, while pro-rights participants favored the free and open flow of data. The latter group expressed surveillance concerns of an increasingly authoritarian state in India which had low judicial oversight mechanisms in place for personal data requests by government agencies and officials.

The third group discussion was an attempt to reimagine the digital economy beyond current and readily accepted narratives. There was a strong case made by digital rights activists that framing the space in terms of a "digital economy" limits policy debates to discussions of market failures and state interventions rather than expanding the space to include other social and cultural issues and stakeholders. One participant felt that in India three reimaginations of the digital economy have emerged around data localization, community data, and data as a public good — euphemisms that emphasize increased government control over citizens' data and the subsequent transfer of this data to the private sector. This is problematic as many state-market negotiations often lack transparency and accountability in India, which has a notorious reputation for crony capitalism. Another interesting conceptualization focused on the physical material extraction that feeds the digital economy, which is as exploitative of developing countries as the metaphorical extraction of personal data that fed the imaginaries of data colonialism.

Finally, there was a series of breakaway sessions on knowledge creation and policy needs for India. The discussions here focused mostly on the gig economy relating to global platforms like Uber and AirBnB and domestic players like food delivery app Swiggy, grocery aggregators like Big Basket, and personalized home services like Urban Clap. The following questions emerged: what kind of data governance standards needed to be put in place? Are labor standards and regulations up to speed with protecting the interests of these gig workers? Do they require sector-specific regulations? And how would anti-trust regulations safeguard the smaller players?

As is often the case at such fora, the two days of deliberations threw up more questions than answers. But what stayed with me was the active engagement on these issues by Indian actors from across the spectrum and some of the similarities of discussions I heard at US and European conferences. What surprised me was the willingness by some of the participants to sacrifice values of privacy and individual rights at the altar of a narrow concept of national development and sovereignty, a disturbing trend in the context of increasing political and social polarization and divisiveness. In this sense, Yochai Benkler’s vision of the Internet, in which networks would enable the free flow of information and encourage the democratization of the information economy and the online public sphere has failed. Instead, the political economy of Shoshana Zuboff's surveillance capitalism model of pervasive and exploitative data collection designed to surveil, target, and micro-target information seems to have won the day.